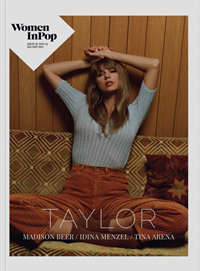

Women In Pop, no. 15, November 2023

by Emma Driver •

Amid the incessant media discourse about Taylor Swift, one aspect of her artistry is often overlooked: her ingenious, powerful songwriting. At fourteen, Swift was the youngest person Sony had ever signed to a music publishing deal, and no matter how her public identity has morphed during the ensuing decades, her determination to tell her stories through her own songs has never wavered. This is nothing less than an expert songwriter at work, and the proof is in every song.

• • •

What makes Taylor Swift’s songs so good?

It’s an obvious question, maybe, but it’s one that mostly goes unasked, as discussions of her colossal celebrity tend to concentrate on everything else: her personal life, her activism, her fans, her wealth, her mega-selling Eras Tour. Wikipedia has a 16,000-word page called “Cultural impact of Taylor Swift”, but her music takes up less than one-tenth of those words. Even in album reviews, her songwriting is often subsumed beneath analysis of her image and her fame.

But no matter how big Swift’s celebrity becomes, or how far she takes her ambitions beyond the music, songwriting is still the heart and soul of her career. As she told an audience of New York University students last year, “Everything I do is just an extension of my writing. Everything is connected by my love of the craft, the thrill of working through ideas and narrowing them down and polishing it all up in the end.”

It’s a craft she has been refining for more than twenty years, a potent combination of musical dexterity, lyrical instinct, focus and sheer hard work. So what is it that Taylor Swift does so well every time she sits down to write a song?

Master of the craft •

Pop music can be a space where stars burn out quickly, unable to continue producing the kind of hits that keep them topping the charts beyond their peak years. Others make a gasp-worthy left-turn every few seasons, reinventing themselves to explore a new musical curiosity or to remain current. Often, it works – at least for a while. “The female artists I know have reinvented themselves twenty times more than the male artists. They have to,” Swift observes in her documentary Miss Americana. Despite noting the ever-present need to find “new facets” of herself that “people find to be shiny”, she has never actually deviated far from her core musical truth: writing songs that reflect her own life and her own emotional conditions.

Nashville was where Swift first found a musical home, but as her writing evolved, so did her sound. “Taylor has always told the truth. She’s written songs from exactly where she is,” observed singer/songwriter Phoebe Bridgers at the 2023 iHeart Radio Music Awards. “Her music shifted genre in the same way life does.”

The progression from the enchanting teen candour of songs like ‘You Belong With Me’, through lavish pop statements like ‘Shake It Off’ and ‘Look What You Made Me Do’, to the thoughtful acoustica of the Folklore and Evermore albums, to the early-hours reflections of Midnights, were never seismic shifts or sudden about-faces. The changes rolled out over fifteen years, all of them recognisable stops on Swift’s journey of growing up – as a songwriter and as a human.

Swift learned a lot from her early Nashville years. Clear themes, storytelling and neat wordplay (“So here’s to everything coming down to nothing,” she sings on ‘Forever & Always’, written at age eighteen) are features shared by great country songs, and her first two albums were seasoned with its flavours – pickup trucks, Tim McGraw, front porches, small towns. But savvy listeners understood that Swift’s songs were never locked to country. “Change the beat and the instruments around the voice, and her songs could work anywhere,” wrote New Yorker music critic Sasha Frere-Jones in 2008. “She is considered part of Nashville’s country-pop tradition only because she writes narrative songs with melodic clarity and dramatic shape.”

Which means that Swift’s musical evolution into mainstream pop didn’t require a radical songwriting shift at all. It was just a matter of embodying her changing self, tilting those songs differently in the studio, and reverting to her own non-Southern accent when she sang. She formed a cohesive musical universe for herself shaped by the gravitational pull of her songs, which in turn have been built from everything she has learned about songwriting, and everything she sees and feels.

“Her unique style was present from the very first record,” says songwriting professor Scarlet Keys, who has taught at Boston’s Berklee College of Music for twenty years and offers a masterclass on Swift’s songwriting. As Swift has evolved across genres, Keys says, she has carried “her initial phrasing, lyrical honesty and proclivity for incorporating musical ideas that create unshakable hooks” into all of her work.

Clearly, Swift’s writing skills are many and deep. First, there’s her lyricism – the imagistic slant of her writing, so much more than bald declarations of I love you, I hate you, come here, it’s over. (She uses those too, but always purposefully, and not for lack of imagination; sometimes ex-lovers are best rebuked in direct terms, as in ‘We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together’.) Sentiments, whether simple or tangled, are braided into bespoke images that bring each feeling to life. We hear about devils rolling dice and angels rolling their eyes (‘Cruel Summer’), treasured scarves and fridge lights (‘All Too Well’), tattoo kisses and Peter Pan (‘Cardigan’), moonstone auras and sapphire tears (‘Bejeweled’), and more.

Swift’s ability to capture complex feelings of love, melancholy, nostalgia, loss and satisfying ‘fuck you’s is second to none. If you find yourself listening to ‘Willow’ as an unexpected message comes through from a wistfully remembered ex, you’ll understand the power of a Swift track to deliver a pure hit of emotion – bittersweet nostalgia, maybe even a strange sense of loss. Try ‘Shake It Off’ when a co-worker asks you passive-aggressively why you’re eating that for lunch. Or ‘Cruel Summer’ when your holiday hook-up turns complicated. Or ‘Mad Woman’, right when someone’s telling you, “Hey, stop being so angry.”

Her subjects may not always be the “big ideas” of the world, but that’s deliberate. Swift once said that one of her missions was to help younger fans navigate complex feelings. “The best thing I can do for them is continue to write songs that do make them think about themselves and analyse how they feel about something and then simplify how they feel,” Swift told NPR in 2014. Scarlet Keys agrees. “Swift’s writing is a musical diary that has given voice to so many young women who needed a way to name their feelings, and she does it in such a beautiful and poetic way,” Keys says. And that capacity has seen her capture older fans too, those who might not be swayed by fizzing synth-pop but who like reflective storytelling that expresses a complex inner truth.

There’s also Swift’s command of melody, the way her tunes fill out her lyrical ideas. It’s always more important for her to finish a thought than to shoehorn it into a predictable structure, yet it rarely feels forced. Lines like “Did you hear my covert narcissism I disguise as altruism / Like some kind of congressman?”, from ‘Anti-Hero’, might feel frenetic in less capable hands, but Swift lets the skittish rhythm teeter on the edge of collapse, then binds it together with near-rhymes and a tight melody that ranges over just a handful of notes.

Songwriter Charlie Harding, who provides fascinating analyses of pop music as co-host of the Switched on Pop podcast, has studied Swift’s writing from the inside out, and explores her craft in the songwriting and production course he teaches at New York University. ‘Anti-Hero’, he says, embodies many of Swift’s key strengths, including what he calls the “melodic math” of the chorus’s conversational opening lines (“It’s me, hi, I’m the problem it’s me / At tea time, everybody agrees”), which perfectly match each other in melody and rhythm. “She has an astoundingly strong sense of melody, of melodic rhythm, of how to build hooks, of imagery, metaphor, rhyme scheme – all of the fundamentals of music, of songwriting,” says Harding. “She has strengths in all of them.”

Swift’s mastery of rhythm is a key feature, and both Harding and Scarlet Keys hear the influence of hip-hop in the way she attaches lyrics to rhythm. For ‘Tolerate It’, from 2020’s Evermore, Swift was offered an instrumental track in an awkward 10/8 time signature – in other words, counting in groups of 10 beats, instead of the more usual 6 or 8 beats – then matched it with a lyric that ranges dexterously over the stresses and offbeats, incorporating just enough space to give weight to particular lines, like “I–I–I … wait by the door like I’m just a kid”. The speech-like pacing of the song’s bridge provides a contrast, where the words of the wounded narrator come out in a rush – “When you were out building worlds, where was I?” The effect is devastating.

By teaming up with carefully chosen co-producers and studio musicians – “in very small teams, usually one other producer, maybe two”, Harding notes – Swift has also maintained control over how her songs sound and how they are presented. Miss Americana documents how she works in the studio, how a song like ‘ME!’, and its video, sprang from her own melodic and lyrical imagination. She doesn’t look to older male producers for inspiration – a lingering stereotype of female pop stars’ success – but is always generating ideas from her own creative engine.

Born to write •

From her first development deal with RCA Records at age thirteen, Swift knew she needed to stand out from other young singers in Nashville’s orbit. But more than that, she needed to write, to make sense of her experiences through the lens of songs. It was the reason she walked away from RCA a year later.

“I’ve been writing since I was twelve, so I had so many songs I wanted people to hear,” Swift told Entertainment Weekly in 2007, adding that “I wanted there to be something that set me apart. And I knew that had to be my writing.”

It was at that point that Sony snapped up fourteen-year-old Swift, the youngest songwriter they’d ever given a publishing deal, yet she refused to feel intimidated by the more experienced writers she was paired with. “I knew every writer I wrote with was pretty much going to think, ‘I’m going to write a song for a fourteen-year-old today’,” Swift told The New York Times. So she arrived at each writing session with “five to ten ideas that were solid. I wanted them to look at me as a person they were writing with, not a little kid.”

Swift’s self-titled debut album of 2006, billed as a country release, was already foreshadowing crossover fame, with ‘Teardrops on My Guitar’ peaking at number 13 on Billboard’s Hot 100 in the US. On 2008’s Fearless and 2010’s Speak Now, Swift began ascending the pop-rock staircase. Red (2012) might have still featured the odd banjo, but Swift and her new production team – including Swedish pop architect Max Martin, who had already produced hits for Britney Spears, Katy Perry and P!nk – decided to usher in a crisper sound. Strummed acoustic guitars were still the key texture, as on fan favourite ‘All Too Well’, but tracks like ‘I Knew You Were Trouble.’ and ‘We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together’ stepped back a little from the fairytale imagery of teen love.

It was 1989 (2014) that really leaned into big pop production, a definite demarcation and a showcase of Swift’s evolving songwriting. Tracks like ‘Bad Blood’ and ‘Clean’ used intricately plotted images to describe relationships gone wrong, while ‘Shake It Off’ harnessed its percussive sax line and pop clarity to deliver an empowerment manifesto. Reputation (2017) was next, defiant and unapologetic, with darker writing on tracks like ‘Look What You Made Me Do’, ‘I Did Something Bad’ and ‘This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things’. Yet amid the skittering, high-toned pop production tools, again the songcraft was recognisably Swift’s, even if she had by then absorbed a few harsher lessons about life.

On Lover (2019), produced mostly with Jack Antonoff, Swift worked with an airier pop palette, while at the same time her songwriting began to tackle wider concerns. A song like ‘The Man’ could have been heavy-handed, but instead it makes its serious point – the way that women in the public eye are vilified but men are not – lightly and catchily. Swift told Billboard she hoped people would “end up with a song about gender inequality stuck in their heads”. And they did.

“I love the way she conveys such a heated topic by avoiding being preachy,” says Scarlet Keys. “She sings it from her perspective of gender inequality, and it allows all women to consider how they might be undermined in society.”

Keys says it’s interesting musically too, as the bass part that runs through the song could be read as “a deeper male voice”, an undertone that represents the bedrock of male privilege in the song. Lyrically, there is deft Swiftian wordplay: “I love how she reinvents ‘man’ within the chorus from ‘If I were the man then I’d be the man’ – it plays with the phrase and transforms it,” Keys notes. Amid songs of love and heartbreak (including ‘Cruel Summer’), Lover offered new subject matter that opened the door to her next songwriting era.

New fans, old critics •

When the pandemic halted live touring in 2020, Swift entered an especially productive period of writing. It had been an eventful few years. She had fought the inadequate payments by streaming services on behalf of all artists, and left her record label, Big Machine. Its new owner Scooter Braun now owned the rights to every album before Lover, so Swift had begun re-recording her back catalogue for the “Taylor’s Version” series.

Then, mid-pandemic, unheralded by any “Big Album Rollout” fanfare, came the surprise release Folklore (2020), produced mainly with Antonoff and new collaborator Aaron Dessner (The National). In the documentary Folklore: The Long Pond Studio Sessions, directed by Swift, she describes Folklore as “the first album where I’ve ever let go of that need to be a hundred per cent autobiographical”. Feeding her creativity were characters parachuting into her locked-down life: “I was watching movies every day, I was reading books every day, I was thinking about other people every day.”

If 1989 drew the line between country and pop, Folklore is the album that elevated Swift from beloved pop queen to, finally, widely respected songwriter. Of course she was already one of the best in the business, but it was the stripped-back aesthetic of Folklore – and its companion album Evermore – that set her lyricism in stark relief, a polished jewel against a simpler backdrop. It brought on board new fans who perhaps had dismissed the Max Martin era of her songwriting, or who were more drawn to the pared-down sounds of artists like Bon Iver, another of Swift’s collaborators on this pair of albums. For anyone who had doubted her skill, there was no denying it now.

Scarlet Keys points to the freshening effect of the change. “Her choice to work with a new producer changed the chemistry in the air and in her writing,” Keys says. “Hearing her beautiful voice overlaid and steeped in new sonic air space was an invention that was both familiar and innovative.” As a pandemic album, it also spoke directly to fans who needed connection and comfort – it had a practical purpose as “a beautiful lifeline”.

Autobiography and outside inspiration sit side by side on Folklore. ‘The 1’ pins down the could’ve-beens of young love, capturing its playfulness and regret; several tracks narrate a fictitious love triangle (‘Cardigan’, ‘Betty’ and ‘August’), while ‘The Last Great American Dynasty’ draws on the real life of socialite Rebekah Harkness. Those story songs are as emotionally truthful and precise as anything Swift has ever written about herself, and the interlocking images and melodic shapes on Folklore never feel rushed.

Evermore, released six months after Folklore and with similar lack of fanfare, continued the expansion of Swift’s songwriting, adding gems like a tightly written murder ballad (‘No Body, No Crime’, with Haim); the heartbreaking ‘Tolerate It’, inspired by Daphne du Maurier’s novel Rebecca; and a song about her grandmother, ‘Marjorie’. Its success led directly into 2022’s Midnights, where late-night ruminations like ‘Snow on the Beach’ and ‘Midnight Rain’ butted up against the word-rush of empowerment on ‘Bejeweled’, and pulsing reflections on fame, love and bad behaviour on songs like ‘Anti-Hero’, ‘Lavender Haze’ and ‘Karma’. The extended versions of the album showcased just how many songs Taylor Swift had up her sleeve, and that number was staggering.

Yes, Swift is a cultural phenomenon, but at the heart of this phenomenon is not celebrity or money or fame: it’s songs. “I think that she is unique in that way as a songwriter,” Charlie Harding observes. “If you want to go be a billionaire, you start an entertainment company, you start a beauty brand – but she’s leaning really hard into her songwriting catalogue. I think that she stands out for the depth of her skills and the speed at which she is clearly able to produce hits, making consistently no-filler-level material.”

So it’s strange, after all the Grammys, and the critical acclaim of Folklore and Evermore, that a dispute about Swift’s capacity as a writer briefly reared its head. Britpop pioneer Damon Albarn, of Blur and Gorillaz, was quoted by the LA Times in 2022 as saying Swift “doesn’t write her own songs” and that “there’s a big difference between a songwriter and a songwriter who co-writes”. To this odd claim, that a co-writer isn’t a songwriter, Swift responded, “Your hot take is completely false and SO damaging”. As did Jack Antonoff: “I’ve never met Damon Albarn and he’s never been to my studio but apparently he knows more than the rest of us about all those songs Taylor writes and brings in.” Albarn, meanwhile, claimed he had been misquoted and did seem genuinely sorry: “I apologise unreservedly and unconditionally,” he replied to Swift online. “The last thing I would want to do is discredit your songwriting.”

The question remains, though: would anyone criticise a male songwriter with Swift’s history, including writing a number 1 album totally solo (Speak Now), for not being a “proper” songwriter? If Albarn was just taking aim at a certain kind of successful woman in pop music – those who are so often historically assumed to not write for themselves – then he was just part of a long line of male “music experts” who have done the same. “Even when a female songwriter is successful, their artistry is often diminished,” writes musicologist Nate Sloan, who is Harding’s Switched on Pop co-host, in a journal article on Swift for Contemporary Music Review.

An element of snobbery about music genres might also be in play. “Distrust is also baked into the fabric of contemporary popular music production,” Sloan observes: teams of pop songwriters are assumed to be mass-producing song parts and assembling them into hits, no creativity in sight – which is not the way Swift writes with her small circle of collaborators. But songwriters in the indie music sphere collaborate too; are they seen as lesser writers? An artist like Phoebe Bridgers offers an interesting comparison. The LA-based Bridgers, an occasional Swift collaborator, is known for her introspective, eloquent lyrics and, like Swift, has attracted a devoted fan base. That she “writes her own songs” is never in question, even though she is very open about her collaborative style: she has several regular co-writers, and while her songs often begin on acoustic guitar, they are expanded into full productions with her trusted co-producers in the studio. Bridgers’ status as a gifted songwriter is taken as lore, as it should be. But still Swift has to keep proving it, again and again.

For proof of Swift’s position at the centre of her process, look no further than the voice memo of 1989’s ‘Blank Space’, which documents an early version of the song. As Swift plays it on guitar and sings, Max Martin and co-producer Shellback can be heard in the background, offering suggestions and whooping with delight. While the lyrics are still incomplete, the contours of the song, one of Swift’s best-loved, are locked in already: key lyrics, melody, pacing and rhythm. In so many ways these early parts are the song. We are hearing, in the words of Scarlet Keys, “a master songwriter and poet” at work.

Influence in all directions •

With such a trajectory, it’s no wonder other musicians cite Swift as a key influence. Her longevity alone has been enough to make thousands of teenagers take up the guitar or start writing songs about their lives, and her country beginnings have been an inspiration for many a crossover act. Commentators also suggest that Swift made space for artists who wrote about their lives in new ways, or who blended genres, like Billie Eilish, Ariana Grande and Dua Lipa.

But what about her musical influence? Charlie Harding feels that Swift’s music making has been so varied and evolutionary that pinpointing her influence in other artists’ music is all but impossible. “She is unique in that all of her projects are standalone bodies of work, so I think it’s hard to demonstrate influence – like, you can’t be her,” he says. “How do you imitate being one of the best at songwriting other than just being one of the best at songwriting? She’s too multitalented to be able to copy.” Olivia Rodrigo has famously owned the inspiration Swift has provided; her song ‘1 Step Forward, 3 Steps Back’ was essentially a new lyric to Swift’s ‘New Year’s Day’, duly credited, and she gave a songwriting nod to Swift on ‘Deja Vu’, due to the (probably deliberate) similarity of its shouted bridge section to Swift’s ‘Cruel Summer’. Harding hears echoes of Swift’s way with melody in Rodrigo’s work but doesn’t think it’s a conscious decision. “I’m sure it’s not quoted intentionally”, he notes.

But maybe Swift’s influence is its most potent elsewhere: when it emboldens pop artists, many of them young women, to not only write honestly about their emotional landscapes but to carefully shape narratives and imagery around them. It’s a style that has been celebrated in indie genres, but now, in Swift’s hands, it is the stuff of the biggest pop hits in the world. If a quiet meditation like Folklore’s ‘Cardigan’ can debut at number 1 on the Billboard chart, then our ideas of pop and of what constitutes a hit song have broadened considerably.

‘Cardigan’ is a powerful reflection on young love; no vocal gymnastics, no synths scissoring in our ears, just Aaron Dessner’s understated instrumentals underneath Swift’s imagery and delicate refrain: “When you are young, they assume you know nothing.” (“I love her use of triplets,” notes Scarlet Keys, meaning the 1-2-3, 1-2-3 count of the rhythm in that line. “Triplets are often overlooked and underutilised by pop writers.”) The song manages to be sepia-tinted and sharply outlined at the same time – there are old cardigans, vintage t-shirts and the smell of smoke, but also black lipstick and bloodstains and scars. The way Swift picks up the pace of the lyrics in the song’s final section captures the rush of an ending, then merges the past into the present with the everyday image of “the grocery line”.

Structurally the song also sneaks in some innovations, playing with the verse-chorus structure (there’s no single identifiable chorus, for instance) but never drawing attention to it. “‘Cardigan’ is an exceptionally strong song,” says Harding. “When I study it, I’m like, whoa, what is she doing? I’ve never seen a song structured in this way. And yet with all of these changes, I actually think she creates a hookier song – there’s all these different hooks that recur. She’s pushing the boundaries of how songs can present themselves, and yet it feels totally familiar. She is really flexing her skills as a songwriter.”

Throughout ‘Cardigan’, Swift’s lyric emphasises “I knew” – because what we feel is a kind of knowledge. We can imagine a classification system of complex feelings emerging from Swift’s back catalogue. There’s regret mixed with euphoria; love mixed with anger; bitterness mixed with determination; and a hundred other combinations. If Swift is still writing with her younger fans in mind, then that makes a powerful message: if we explore what we feel, we do know something after all. And when that message is so skilfully crafted, it will reach those who need to hear it in the most meaningful and memorable way. •